Populating the Planet

A two million year journey begins

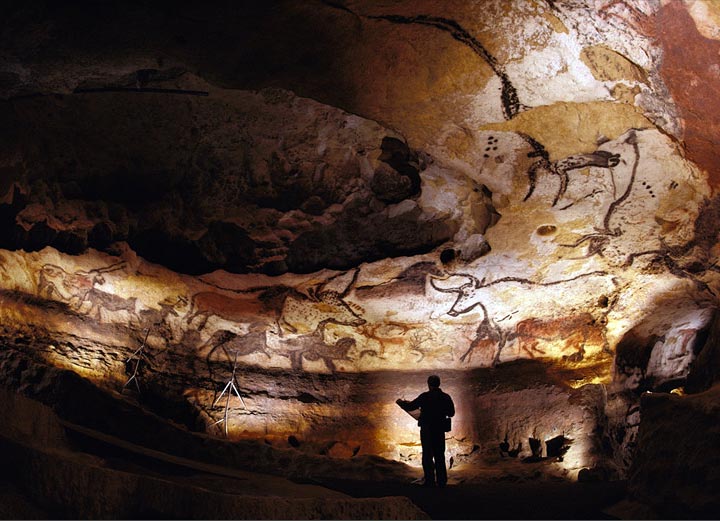

Our story, the history of travel, begins here, with our early ancestors, specifically the type of human known to science as Homo erectus, which lived from about two million years ago up until about 150,000 years ago. Homo erectus was remarkably unique and sophisticated in a number of ways: this was the first type of human to control fire and one of the first to use stone tools. And although we now know the species originated in East Africa, the first fossil discovered was in 1891 in Java, an Indonesian island some 5,000 miles away as the crow flies.

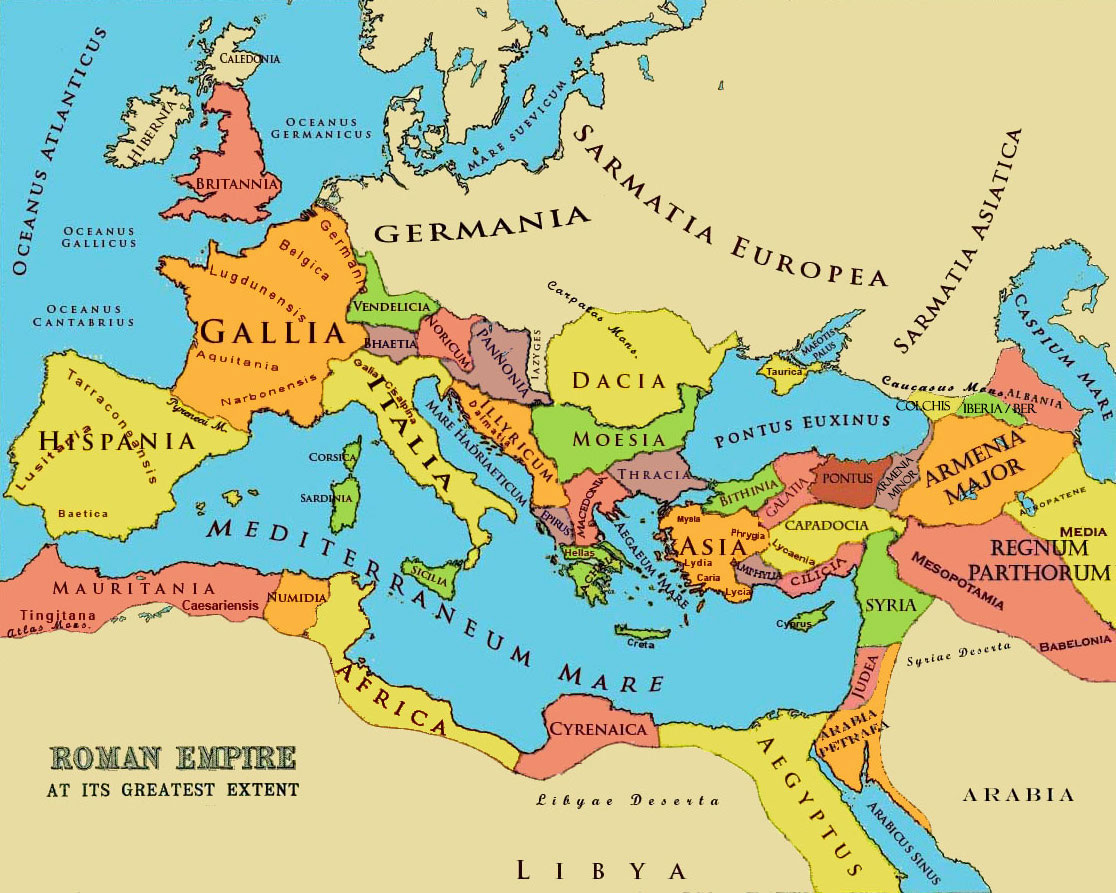

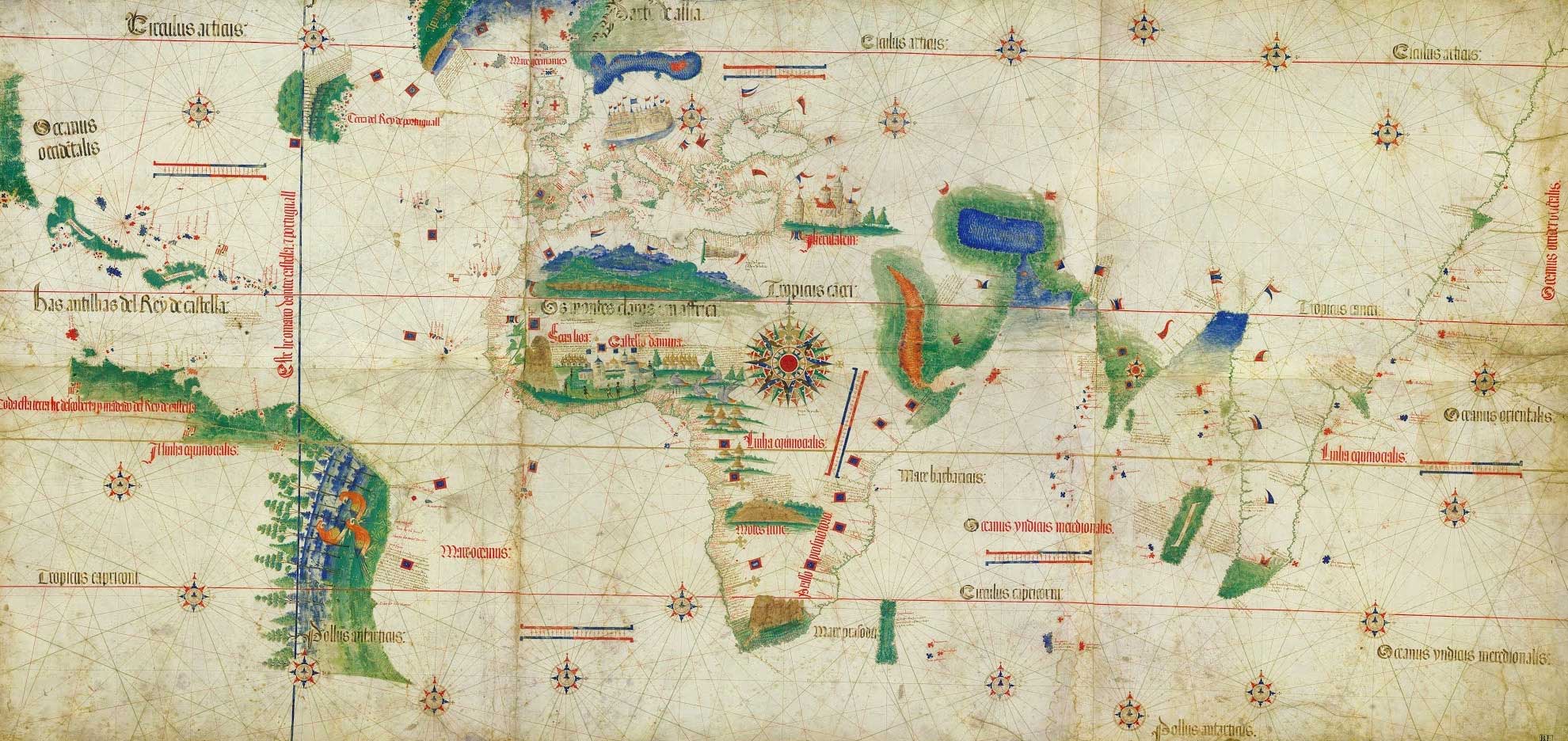

Of course, Homo erectus wasn’t a crow and it couldn’t fly, and although there is some evidence to suggest the species created basic rafts, it certainly didn’t invent anything which could cross thousands of miles of Indian Ocean. The only plausible answer, which has been confirmed by other fossil finds in the last century, is that Homo erectus saw fit to gradually leave Africa and colonise other parts of the world, notably the landmasses of Europe and Asia.

The first of the great human migrations had begun, and so too the history of travel.

It’s a peculiar thought that the human race once comprised several different species: our dazzling egos rarely permit us to imagine any other life form being remotely similar in terms of intelligence – even our own family, so to speak. But the fact is there were many, and all are now extinct apart from one: Homo sapiens, from which every human alive today is a direct descendant.

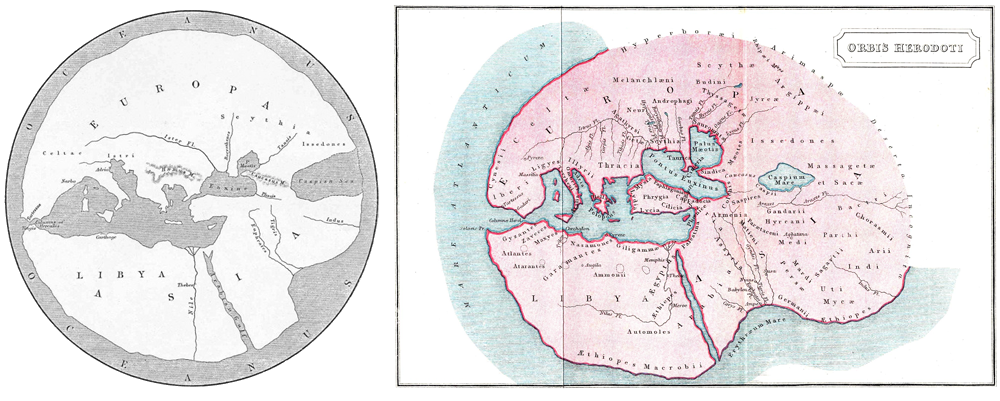

Like other human species, Homo sapiens – that’s us – originated in Africa, with the earliest fossils dating to approximately 200,000 years ago. And like Homo erectus, we migrated out of Africa and began colonising other parts of the world, with the first intrepid explorers flying the nest about 70,000 years ago.

Unlike Homo erectus, we travelled much further, most notably to Australia and the Americas, which meant that by about 10,000 years ago every major inhabitable landmass on Earth supported human life.

Our willingness to travel and explore had allowed us to populate the planet.

Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race. The heathens poured out the blood of saints around the altar, and trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God, like dung in the streets.

Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race. The heathens poured out the blood of saints around the altar, and trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God, like dung in the streets.

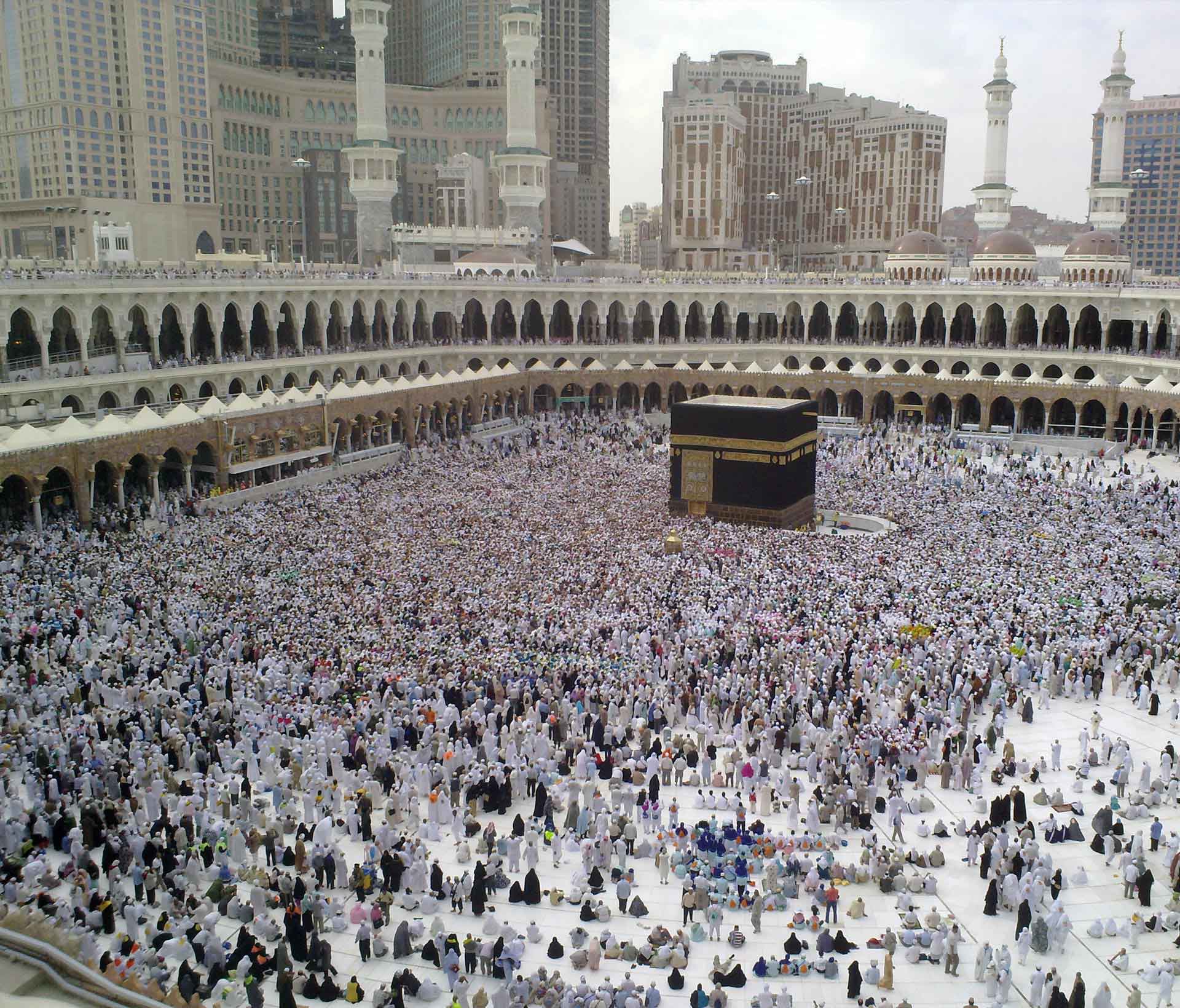

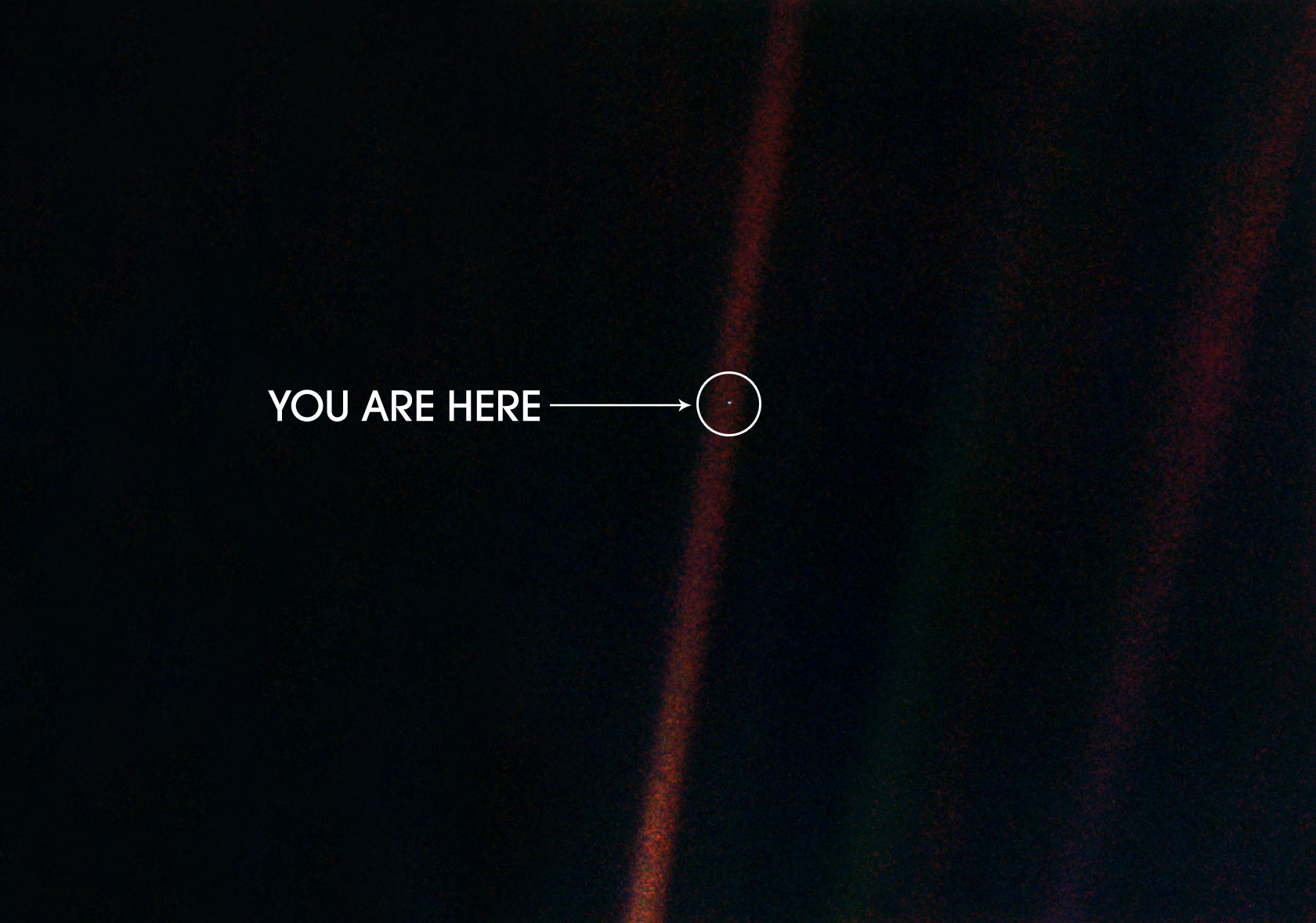

That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every 'superstar,' every 'supreme leader,' every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there - on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every 'superstar,' every 'supreme leader,' every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there - on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.